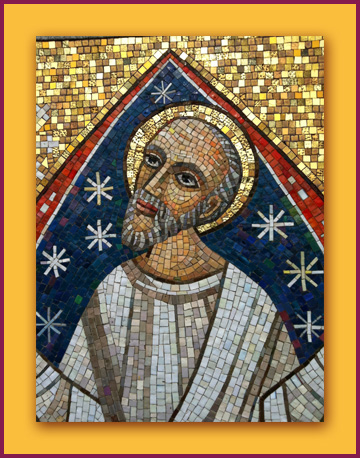

My wife and I live in an older “inner ring” suburb just a few blocks outside the St. Louis city limits. Many years ago this must have seemed the right place for cemeteries, because we’re surrounded by a half dozen of them. Just north of our subdivision is Resurrection. I think that’s about the best name there is for a cemetery. Within Resurrection are a dozen or more large monuments that feature beautiful works of art by the Ravenna Mosaic Company. These mosaics have at once an ancient and contemporary sensibility. Byzantine art from the 10th century, upon which this style is based, strikes me as oddly modern. I’ve borrowed from this aesthetic quite a bit during my career as a children’s book illustrator. There’s something about it that appeals to my bent for reflection and Byzantine art is simply great graphic design. Plus, I find the stylized figures and scenes to be quirky enough to suggest an inexplicable delight, especially when peppered throughout a cemetery.

I say inexplicable, because graveyard art doesn’t immediately produce delight. The vast majority of monuments are somber, staid, and deadly serious. Then you happen upon these scattered gems and a light goes on as the sun bounces off their multicolored chips. These are images of hope in the midst of a hopeless landscape. While this cemetery is named Resurrection, the reality is that every grave is occupied. Unless one construes that Resurrection means souls flying off into a disembodied Heaven (and that is not what the word means), it will seem the place was misnamed. Maybe it’s the artist in me, but when I look at these beautiful works, I sense an insistence that this place is not a final abode, but a temporary and sad necessity in a world where death still happens. For the time being.

The images on these markers are meant to catechize, that is, to teach faith. They aren’t just religious images decorating the graves of those who could afford such luxury, but picture books that guide our eyes past the gray city of death to the future city of life where God makes his home with his people. There is great whimsy in that story, not because it’s silly make-believe, but because it’s real and solid. I’ll call it eschatological whimsy. Eschatology is about final, or ultimate things, which means it’s about resurrection. Real, solid, resurrection from the dead. Real dead people coming back to real people life. Physical, touchable, inexplicable. Whimsical even, because death gets killed and those made alive again get to laugh forever.

It will be said on that day, Behold, this is our God; we have waited for him, that he might save us. This is the Lord; we have waited for him; let us be glad and rejoice in his salvation. Isaiah 25:9